Lindsey Clark

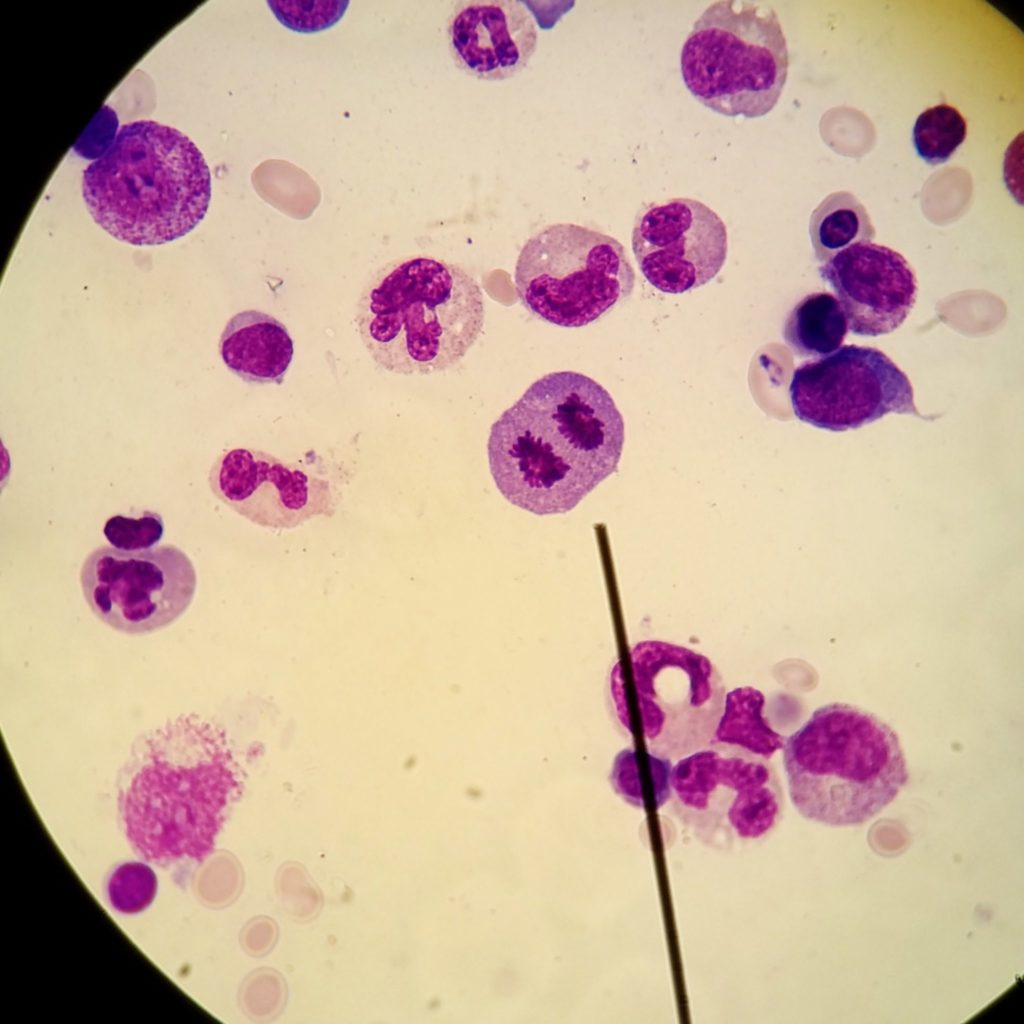

A photograph of a cell undergoing mitosis found in a bone marrow specimen.

Lindsey Clark, M.P.H., is an assistant professor in the UAMS College of Health Professions Department of Laboratory Sciences.

Lindsey Clark

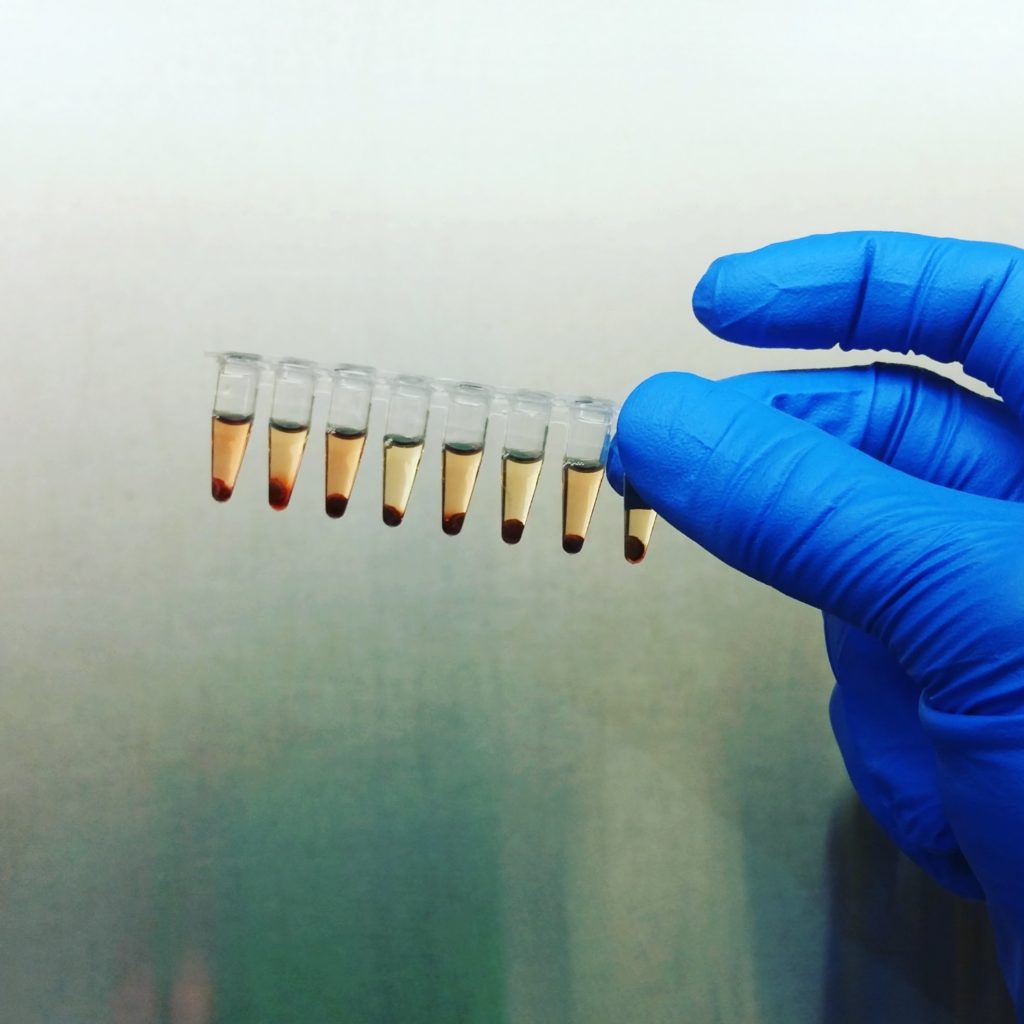

This photograph shows one step in the DNA extraction process. Working in a molecular laboratory is enough to remind you that sometimes, the small things do matter.

Lindsey Clark, M.P.H., is an assistant professor in the UAMS College of Health Professions Department of Laboratory Sciences.

Jonathan Spradley

This image illustrates that the practice of medicine is a collaborative effort. Individual providers may feel a large responsibility for a patient’s care, but effective care occurs when many providers’ perspectives and skills are brought together to give a complete bird’s-eye view of a person in need and how to care for them.

Jonathan Spradley is a medical student at UAMS.

Jonathan Spradley

Hospitals tend to hold strongly positive or negative associations for people: those of inspiring medical expertise and research or painful memories about themselves or loved ones. Often overlooked are the quiet, routine moments that occur every day from maintenance to landscaping to window washing that allow hospitals to stand amidst their chaos within.

Jonathan Spradley is a medical student at UAMS.

Jonathan Spradley

This image is a reminder of the intersectionality of healthcare disparities between geographic location and gender. Women, such as this one in Essaouira, Morocco, are tasked with difficult journeys of trying to participate in healthcare systems made inaccessible to them as doors are repeatedly closed in their paths.

Jonathan Spradley is a medical student at UAMS.

Jonathan Spradley

This image represents the “art of medicine” – the artistic and creative expression that can come from technical skills or seemingly black & white components. As with learning to play the proper keys on a piano to create music, the overall outcome of medical education should be to reach beyond scientific knowledge and create personalized, meaningful treatment plans and relationships with patients.

Jonathan Spradley is a medical student at UAMS.

By Elizabeth Hanson

First, she told him that winter had come.

That the ground was hard

And the soil cold.

That the seeds were stowed safely away

Somewhere deep, waiting

For the warm season to come.

Then, she told him the snow had melted.

That the orchard was a lake

And the earth too wet.

That they must wait for it to dry

Because seeds, well, they couldn’t swim!

They needed dirt, soft yet strong

Where roots might anchor,

Tangle and grow.

Next, she told him that a daffodil had bloomed.

That it stretched tall,

And yellow beneath the orchard’s branches.

That above, buds had formed,

Blanketing the bark

The way his quilt covered him.

If only he could hang on.

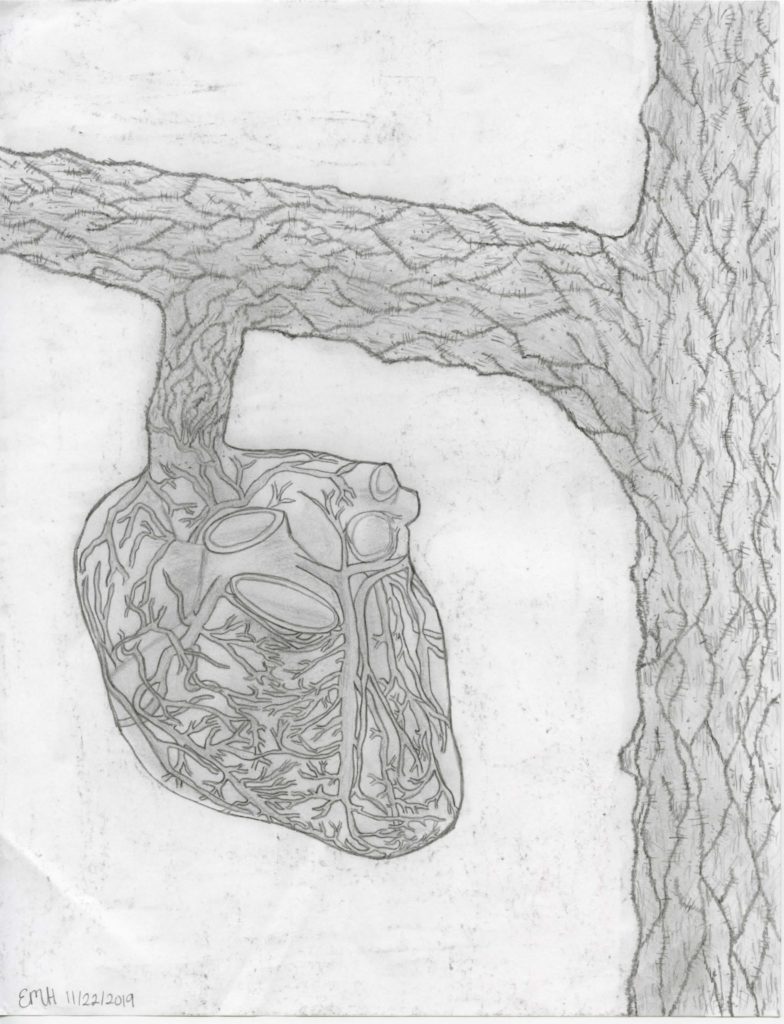

Last, she told him that his turn had come.

That he would sleep and then wake

With the heart that had grown

From the seeds they had saved.

That he might dream of the day

She had walked among the orchard rows

In the place where love grew on trees,

And hearts could be plucked

Like apples in the fall.

Elizabeth Hanson is a resident physician in the Emergency Medical Department at UAMS.

By Erick Messias

Nobody would call him doctor anymore. It turned out to be harder to get used to Mister Maia than to Doctor Maia, which had happened to him after moving to America for medical residency some forty years before these days. It gave him pause to hear Mister Maia, as if this was some long-gone relative from the old country. Yet, he was now Mr. Maia except to a couple of Mexican nurses who called him Señor Maia, trying to please him but only succeeding in irritating him a bit further. He did not correct them; it had been many years since the days he explained Brazilians spoke Portuguese, not Spanish, and their capital was Brasilia, not Buenos Aires.

The nursing home’s brochure had exaggerated, as marketing pieces usually do. In reality, damp and faded mini-apartments substituted for the airy and bright little cottages in the pamphlet. The staff seemed to make an honest effort to be polite and helpful, he recognized. His children also seemed sincere in believing the brochure and the apartment manager, a dignified and patient African American woman in her fifties.

The kids had helped their old man move to the nursing home after their mother, his wife for those same forty years, had died. He was now single again, and their children, one a computer engineer living somewhere in California, and the other a staff writer at some New York web-magazine, pleaded with him to leave the large house in the suburbs of Little Rock for the nursing home in the sprawling West Little Rock enclave, aptly named Mount Elysium.

He offered little resistance. He knew the alternatives were few, staying in the house impractical, and the invitations to move to California or New York sincere illusions. He knew there was no return path to the old country, where his childhood had once been and where his own siblings were still living. After all, Brazil was now the old country, where he knew few people and even fewer knew him. The old Little Rock house where they had raised their children, where he and his wife had had so many brief breakfasts and long dinners was too old, too big, and too full of used-up furniture and memories; much like him. The children did it all with American efficiency, and in little more than a week everything was gone; the house was on the market, and he moved to Mount Elysium nursing home.

His daughter had insisted he get a room with a view. The manager had promised her to find her father the best views of the whole complex. The daughter believed the manager as she had believed the brochure: wholeheartedly. His son had agreed and made sure everything was set up for him at the bank and with the real estate company. Mr. Maia drove both kids to the airport since he could still drive around town in the semi-new Toyota Camry. Returning from the airport, he drove back to the old house instead. Old habits, old pathways and turns taken for forty years had left deep impressions in his brain. He saw the “For Sale” sign, took a deep breath, and drove himself to the nursing home. They were not the kind of people to make a fuss about things.

He asked the guard at the entrance how to get to his new home, his benign incarceration in a room with a view, he told himself as he parked. He was sure it would be a view of some mountain ridge since they were far from the Arkansas River.

He had to admit the little apartment was not bad. It was clean, sparse and quiet. As a young man with literary aspirations, he would have called it spartan. He was finally alone after the back and forth of the last days with his kids in town. He set the clock in the automatic coffee maker for seven in the morning and went to bed at ten, falling asleep over a science fiction book. He fell into an exhausted slumber and woke up to the smell of fresh coffee.

The window was closed so he decided to finally check the view he had been promised. By his own estimation, it would be a front view to Pinnacle Mountain, one of the locally famous Arkansas landmarks. He opened the window and was surprised to see some thick tree foliage blocking whatever view would be in place.

He was working himself up to complain to the manager when he noticed something unusual about the tree. It was not one of the ubiquitous oak or pine trees seen in most Little Rock yards. He looked and looked and, after examining it carefully, finally recognized it was a Jambo tree, just like the one they had in front of their house in the Brazilian northeast coast so long ago. He looked at the elliptical, large, shiny leaves, at the curvy, bright red fruits; he remembered how difficult it was to keep the neighborhood kids from throwing rocks to get those fruits down. How many times his father had promised to cut down the tree to avoid the shower of stones when the tree was in season. He had not seen a Jambo tree in many years, and he now could go to his window and look at it. He looked further, past the foliage, and saw the tall gray wall that surrounded the front neighbor’s house, the wall that showed those neighbors did not think they belonged in the low middle-class street, the wall reminding them there were other, more important people in town. The neighbor was a district judge, or so he was told because he never saw him or his children, only a car coming in and out of the walled house. He looked to his right and saw the other house across the street, the one that belonged to the old lady who had married a Spaniard and whose father had given name to the street on which they lived. She was always trying to be friendly and make conversation, especially after her Spanish husband had left her for another younger Brazilian woman. Her house had a large backyard filled with goiaba and siriguela trees, and when in season, the kids, including him, would invade the orchard and have a tropical feast. He looked to the window sides and noticed the same chipped, cheap paint he and his father had coated many times. The same little chips of paint he would pull when nervously talking to the neighbor’s daughter, whom he thought was his first love. He felt his nose fill up with the tropical smells of his childhood.

He noticed some drops of rain and had to close the window. A cup of warm coffee started his day, and he went to his new routine of news on the internet, driving around by himself to find a place for a light lunch, and coming back for a movie at the dollar theater or on the computer. Each morning, his coffee machine did not have to wake him up as he was itching to enjoy his view again.

He opened the window expecting the Jambo tree and was greeted by the great sandy plains of the South Atlantic. It was the green beach of his childhood, the one that had given his state the nickname of Land of Green Seas. The air smelled of the salty breeze, and he felt tiny grains of sand hitting his face. He saw the long fingers of the breakers holding the tides to protect the city; he saw in the distance a few jangadas, the small rafts used by local fishermen to bring home their oceanic harvest. Along the shoreline, there was a runners’ lane where people would do their morning walking and running, and along with it the many sellers of local arts and crafts. He took a deep breath and shut his window, sitting down in front of the computer for his morning coffee and news.

Next morning, he walked slowly to the window. He put his hand on the small latch and stayed there longer than expected. Instead of opening the window, he moved his fingers between the louvers and peeked outside. A small house loomed on the other side of a cobblestone street. The sidewalk in front of it was a couple of feet higher than the street level. He remembered his grandfather telling him that the high street level was done to prevent the floodwaters to get in the house. That house across the street was a bar, and he remembered peeking through the window at night from his grandparents’ house in Jaguarana, the city where his mother would take him and his sister on vacation every year. His grandmother did some peeking too; to see who was going to the bar, how long were they staying, and who was taking them home. He had his own reasons to look since the daughter of the bar’s owner, a girl with long black hair, would come help her father from time to time. That was their own version of beer commercials pairing women and alcohol; and to him the best.

On a cloudy Little Rock morning, he opened the window to the dark corners of a motel room. What he saw lying in bed, getting undressed nervously, was a young, blond, and pale eighteen-year-old girl he recognized immediately as his wife of forty years. He saw the quiet pride in the young body; he saw the white skin punctured by birthmarks, and he saw her long hair running all the way to the small of her back. She would never have it as long as that again. At first, they would do just that, lie in bed in awe of each other’s body, youth, and inexperience, afraid that if they had sex suddenly everything would change in some unpredictable way. Eventually they did and it did. They did not know at the time they would be spending the rest of their lives together and witnessing the inclement effects of time on their firm muscles and smooth foreheads. He did not know at the time she would only get more beautiful to him, after each child, after each year.

And so, his final routine was born. It would not last long but it lasted enough. One day the nursing home cleaning crew found him dead, sitting in the recliner by the window. His children came again from the coasts to Arkansas. His son talked to the nursing home manager, and she told him about a placid pattern and a peaceful death. She told him he had a smile on his face when they found him looking out the window. His son imagined she told that to all grieving children, and he chose to believe it.

The son remembered his sister insisting on the room with a view, and for some reason he could not discern, he remembered one of the many sayings from his father, “The best part of doing a good job is to be able to look at it when you are finished.”

His son looked at the view outside and saw Pinnacle Mountain looming in the background. He was reminded of how beautiful the Natural State was, and then he shut the window.

Erick Messias, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., is a professor of psychiatry and the Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs in the UAMS College of Medicine.

By Morgan Sweere Treece

Lights, bright lights, blurry lights, headlights, flashing ambulance lights, EMT flashlights, fluorescent hospital lights. That’s probably some of the only things I actually can recall about that night.

November 15, 2012. It was a chilly- Thursday evening, the time of year when all the leaves have just fallen on the straw-like, browned grass as everyone got ready to pull out their fuzzy, woolen scarves. It seemed no different from any other day. I got up, went to school, and everything was normal, but when I got home, I heard some of my favorite words leave my mom’s mouth: “Your cousins from Fayetteville are in town and headed out to the field.”

My cousins were on break from college and home for the week, which only happened once in a blue moon, so it was breaking news to me. What did this rare occurrence mean? Extreme night mudding!!! In mere seconds, I was hopped up in my car and sped on my way to the field where we took the four-wheelers each time the cousins visited town. It could actually be compared more so to an obstacle course instead of a field, the way the trees seemed to randomly spurt from the rocky soil, with large boulders and hills lining the moist, unmowed fields. We unloaded the four-wheelers, still caked with the old, dried mud and dust from our last night riding event. Soon enough, the four of us were zipping over the rough and ragged barriers toward our designated finish line, the dry, brown grass grazing our ankles and bitter wind gnawing at our cheeks.

One of the next memories I have of that momentous evening is waking up, confused, hardly able to see, completely unable to think, having been rolled over by multiple unidentified hands. In what seemed like hours but was actually seconds after that, I tried to understand what was happening. I recognized no one around me. My mind was unable to comprehend the situation. I heard shouting – in the back of my mind, a perceived distant memory. “HELP! She’s gushing blood! Morgan!”

EMTs, paramedics, cousins, and my mom all screeched in unnerving anxiety. They attempted to relieve the aching pain from my marred face and body soaked with blood. I couldn’t feel the pain, but I knew it was there somehow. I couldn’t talk. I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t think. I had a major migraine, and I could feel the blood gushing from every pore of my body. The blood started to dry and left an amber stain all over due to the icy, winter-like wind. I had no idea what was happening and no one took the time to explain it to me. I could see the wrathful, crimson liquid encompass my line of vision in mere seconds, and I even tasted the iron soaking onto my tongue. Then all went black. The next 14 hours of reconstructive surgery and stabilization were marked by panic, worry, and God’s miraculous and loving work in the hands of many talented ER physicians and surgeons. The surgery was tedious but flawlessly executed in the end, soothing news to my anxiety-filled family in the waiting room. Then I woke up in a haze. The intense, sterile hospital room filled with dazzling yet blinding fluorescent lights and vaguely familiar faces left me still unable to comprehend just where I was, or even who I was. The copious amounts of drugs in my body overtook my mind, and the five or so hours after I awoke are mostly a fuzzy cloud in my memory.

Several days later, I regained complete alertness in a sober stage. Someone told me that in my first spoken words after I roused from my morphine-induced slumber of surgery, I solicited the immediate presence of my mother, my boyfriend, and (of course) a Sonic Coke — clearly, my priorities were pretty straight, even as a pain-filled, drugged-up girl. I knew exactly what I wanted and what I would have missed greatly had I never seen those three things again, however trivial the last is.

When I woke up in the hospital, the first things I actually remember were large dark black and blurry mounds blocking my view. I blamed this “tunnel vision” on my cheeks, which had risen to an insanely abnormal height due to the entire swelling of my face. However, now that I think about it, symbolically this block in my sight may have actually been my seeing less temporarily so that I could see more now. It took a full six months – in what I called “puffy girl problems” — for all the inflammation to disappear, but after I finished being the metal chipmunk I was and began to regain the feeling in my face, I realized how important the experience was to me, however awful it may have been. And trust me, it was really awful.

The best and worst experiences in the lives of people always are the most important memories because those experiences have the greatest impact on the way people live. I consider my ordeal as one of the most painful and grueling experiences I have had at this point in life in which I utterly shattered every possible bone in my face into 23 pieces, including both jaws. I had a concussion and practically became The Terminator with four metal plates, four metal screws, and large wires and bands that starved me for six weeks. However, I also realized it was one of the greatest blessings in my life because I realized the most important things in life: God, family, and friendships.

Even almost a year later, I often get caught up in the almost regular conversations imbued by questions like “You broke your…face?” “Did it hurt?” “Can I touch it?” “You have metal in there?” “What happens when you go through airport security? Or if you get slapped?”, and the most frequently asked “Do you look different?” or “Do you like it?”. Those last words of blunt inquiry always seem to strike me the most, although it is only a frivolous query to others. The words seem to stop me dead in my tracks more than anything anyone could probably ever say to me. I’m not different. I’m still me. I still feel like me. But I’m not. I didn’t recognize myself in the mirror for almost three months after my surgery because, in truth, I am different—on the outside and the inside. Not only did my (still groundbreaking) stupidity and recklessness teach me not to attempt ramping a rocky slope at top speed on a four-wheeler in the autumn dusk just because I was dared to. It taught me that I — as much as I want to be or think I feel most of the time — am not Superman. I shouldn’t live like it either. I can’t live like I’m invincible, like I can’t get hurt or suffer any consequences, like I’ll never get caught doing anything bad, like I can save everyone around me from everything. It might be an insane joyride in the air to feel so immortal, flying even, but the ending sensation of cracks, snaps, stinging, and wearing a warm, sticky sweater of blood sure did crack my thick skull as I hit the ground. I learned from all that.

However cliché it may be to say that the lesson learned here is carpe diem or “YOLO,” it isn’t to say the latter — that life isn’t forever and high school isn’t forever, and I learned to no longer treat those periods in such a way.Waking up in that uncomfortable hospital bed, drugged to the maximum, looking like a hideous, Botox-gone-wrong patient, but still surrounded by tons of worried, sympathetic faces of loved ones, along with various flowers, cards, and balloons — I couldn’t help but feel more like a puffy little princess than the monstrosity of a monster I was then portraying. It’s a medical miracle that doctors were able to piece back together a face shattered into 23 pieces, much less to make the end result even remotely close to my previous appearance. I learned to appreciate the precious jewel of life and the irreplaceable emeralds and rubies surrounding my bed 24/7 until I was released to go home. The sudden realization I had when awaking in that bed was not the normal “blinding light” that near-death experiences often produce, but more a recognition that I should live my life better, treat those I love better, and graciously accept the undeniable truth that I hadn’t been doing these things before. I often ponder, what if I hadn’t woken up? Had I told my family I loved them before I left? Did my friends know how much I cared about them? Was there any doubt that I lived my life for God? Was my time here enough? I never wanted to question it again. I was never afraid of dying — just, not really living, and not living the right way. I truly believe that God has given me another chance in this life; it just took a quick slap in the face (or rather face plant) to realize how I’m supposed to be living my life. Don’t wait to get your life together or to go for your goals — the time is now. My accident was a traumatic eye-opener, although it seemed quite the opposite through the six months of swelling. The genuine truth about “forever” is that it is happening in the present moment. Living life to the fullest is an understatement for me; I want to live life to the point of super saturation, to the point that I am constantly overflowing with unparalleled joy, kindness, and gratitude. It is vitally important to live each day as if it is my last, to tell people I love them while I have the chance, and to never leave any words unspoken. The lesson learned? Don’t put off things until tomorrow. What if there is no tomorrow? Live your dreams now. Say it. Do it. Appreciate it. Love it. And whatever you do: Always, always, ALWAYS wear a helmet.

Morgan Sweere Treece is an M.D./Ph.D. student at UAMS.

By Diane Jarrett

The doctor stood there looking at his patient with a mixture of compassion and horror. Somehow the treatment had gone terribly, terribly wrong. What had started promisingly as innovative therapy for serious trauma wounds had resulted in the ultimate unexpected side effect.

The patient had been transformed into an alligator.

Perhaps this is not surprising when you consider that the doctor had been possessed by the devil only 15 years earlier. Oh wait — that turned out to be just a bad dream.

In a way, all of the above is a dream, from the standpoint that I’m talking about movies and movie doctors as portrayed by George Macready (1899-1973), a stage, film, and TV actor whose career spanned from the 1920s to the 1970s. Along the way, he was a devil-possessed doctor in The Soul of a Monster (1944) and an awesomely inept endocrinologist in The Alligator People (1959). And you thought you had personal problems, or had treated patients with scaly skin.

What has this to do with Family Medicine, you ask?

My department chair said basically the same thing when I told him that I had just obtained my first national publication, not in Family Medicine or JAMA or any of the journals that classic film fans would call the “usual suspects.” No, my debut was in Films of the Golden Age, and my topic was the life and career of George Macready. Macready is best remembered for playing Rita Hayworth’s husband in Gilda (1946), director Stanley Kubrick’s cruel World War I general in Paths of Glory (1957), and the patriarch Martin Peyton in TV’s Peyton Place from 1965 to 1968.

My Macready publication, which in part addressed his roles as physicians in The Soul of a Monster and The Alligator People, did nothing for my career advancement. Publishing essays about the lives of classic movie actors doesn’t count in Family Medicine for promotion, tenure, or anything like that. Zilch. No matter how often I’m published in film history journals (eight times so far) or how much acclaim I receive in film circles, the medical profession is unimpressed.

I’m not a medical doctor. I don’t even play one on TV. My background is in education and journalism, and I came to work in a Family Medicine residency program long after I diagnosed myself as having a serious case of classic film passion. Writing about clinical topics or education related to clinical topics had never been on my radar. It is now, but my heart continues to compel me to spend some of those hours that might be assigned to Annals of Family Medicine on researching the lives of actors such as William Boyd, Richard Todd, and others.

Being a published film historian is not the same as being published in a medical journal, of course. Still, I can’t help but wish that my avocation could be considered as support for my vocation. Thus far it seems unlikely, though I point out George Macready’s medical “connections” at every possibility.

Since promotion is important to me, I’ll continue to faithfully seek opportunities to publish in periodicals that count, kind of like the group called Dr. Hook & the Medicine Show, in their song from the 1970s, sought to be on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. (That wouldn’t have counted for them either, despite having the word “medicine” in the name of their band.) In my personal time, though, I’ll continue to research and write about actors who might have at least played doctors in the movies.

Meanwhile, I can only hope that someone comes up with a peer-reviewed journal entitled Medicine in the Movies.

Diane Jarrett, Ed.D., is the Director of Education and Communications in the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine. She is also the Assistant Director of the residency program.