UAMS Alumnus and Pioneering Transplantation Surgeon

Timothy G. Nutt

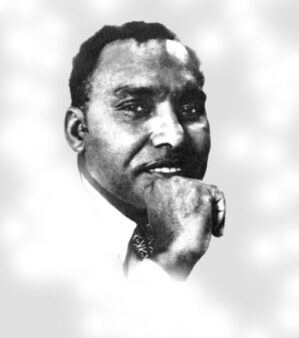

Of the hundreds of prominent graduates of the UAMS College of Medicine in its nearly 150-year history, Dr. Samuel Lee Kountz stands out for his work as a pioneering kidney transplantation surgeon. Born in the Mississippi Delta, Kountz grew up during the Jim Crow era of segregation. Despite this, Kountz became one of the world’s most respected physicians before his untimely illness and death.

Kountz was born in the small Southeast Arkansas town of Lexa (Phillips County) in 1930, the eldest son of Rev. J. S. and Susie Kountz, a Baptist preacher and farmer, and a midwife, respectively. Kountz attended a one-room segregated school in Lexa and, for a brief time, boarded at a Baptist school in the town. Ultimately, he graduated from Morris Booker High School in nearby Dermott (Desha County) in 1948. That same year, he applied to Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College (AM&N; now University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff), but he failed the entrance examination. AM&N President Lawrence A. Davis Sr. admitted Kountz to the university after the student appealed to him, impressing the college administrator. Despite his rocky college career, Kountz excelled in his studies, graduating third in his class with a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry in 1952.

It was at AM&N where Kountz met U.S. Senator J.W. Fulbright, who encouraged him to continue his pursuit of becoming a physician. Kountz’s interest in medicine could be traced to a childhood memory, when he helped an injured friend to a doctor. Inspired by the kindness and care exhibited by the doctor to his injured friend, Kountz decided to become a doctor. After his graduation from AM&N, Kountz earned a Master of Science degree in biochemistry from the University of Arkansas in 1956, and graduated from the University of Arkansas School of Medicine (now UAMS) in 1958.

Post-graduation, the newly-married Kountz interned at San Francisco County General Hospital. There, in 1959, Kountz participated in the first West Coast kidney transplant. Later, Kountz spent seven years in surgical training at Stanford Medical Center, where he was chief resident and experimented in transplants and researched ways and medications to reduce transplanted organ rejection. In 1967, Dr. Kountz transferred to the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), where he led the Kidney Transplant Service. One of his many achievements at the University was developing with his colleagues a prototype of a machine to preserve kidneys before transplantation. This machine—known as the Belzer kidney perfusion machine—is able to preserve kidneys for up to 50 hours from the time they are removed from the donor’s body. Kountz also conducted a study that ultimately proved that a patient could successfully receive a kidney from an unrelated donor, whereas before it was thought that only relatives could donate organs.

After seven years at UCSF, Dr. Kountz left and became chief of surgery at the State University of New York-Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn. There, he continued to perform kidney transplants while still advancing the field, including improving tissue typing which improved the success rate of transplantations. Throughout his career, Dr. Kountz performed over 500 kidney transplants. In 1976, Kountz performed a kidney transplant live on the Today show in front of national audience, to emphasize the importance of organ donations. After the show, over 20,000 people signed up to be a kidney donor.

One of Kountz’s reasons for moving to Brooklyn was to improve the health care available to the Black community. Once, he sat in the emergency room at the Downstate Medical Center to personally observe the treatment given to the waiting patients. This compassion for patients could be traced to his childhood, when Kountz accompanied a friend to a doctor.

In 1977, Dr. Kountz traveled to South Africa to serve as a visiting professor, and fell ill soon after with an undiagnosed neurological disease. Dr. Kountz suffered brain damage, rendering him unable to speak and walk for the remainder of his life. After a career filled with innumerable successes, Dr. Samuel L. Kountz died in 1981. He was survived by his parents, two brothers, his wife, and his three children.

Millions of people have benefitted from the pioneering work of Dr. Kountz, and his is one of the inspiring stories that make up the history of medicine in Arkansas and UAMS.