By Hyginus Ukadike

“African Landscape” is a watercolor by Hyginus Ukadike MSW, MPA. He is a psychological counselor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

By Hyginus Ukadike

“African Landscape” is a watercolor by Hyginus Ukadike MSW, MPA. He is a psychological counselor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

By Charles Sandor, M.D.

“Many have asked me where my talent for art comes from. I always say the Lord and my mother who is a gifted artist. At a young age I would watch her paint and she would always teach me various techniques and give me art books to study style, composition, color, inspiration.

Over the years I found myself gravitating towards portraiture and landscape painting. Capturing the beauty and essence of nature and people was the highest compliment one could achieve. I’m naturally inclined towards the shadow and earthly tones, which my mother would tease me about saying that I find any reason to put dark colors into a painting. Contrast adds depth and richness. She can mix incredibly vibrant colors and I still ask her for her advice when I need to mix a bright color.”

Dr. Charles Sandor is a graduate of the UAMS Little Rock Family Medicine residency program.

By Charles Sandor, M.D.

“For me, art is the ultimate juxtaposition of evocation and catharsis. Everything begins with whisper of an emotion that builds into a whirlwind and it has to be expressed. Every artist will describe their muse differently; this is just my explanation for the passion.”

Dr. Charles Sandor is a graduate of the UAMS Little Rock Family Medicine residency program.

By Angie Porter

“Solitude” is a painting by Angie Porter. She based the scene on ideas from her travels around the world.

By Angie Porter

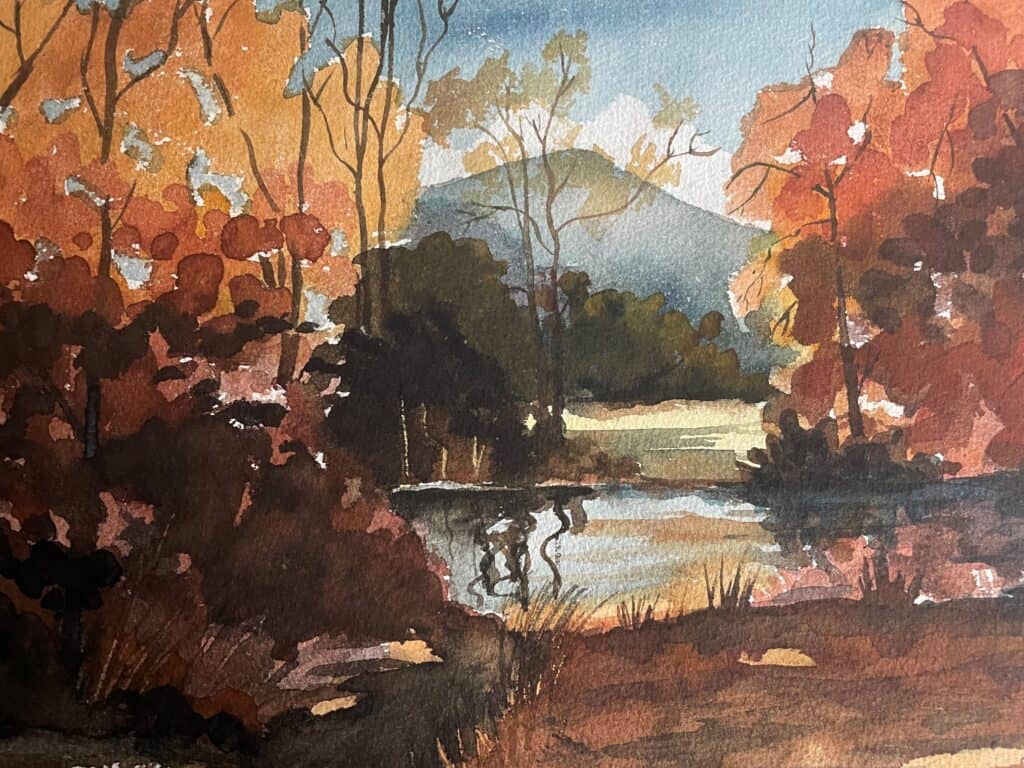

“Autumn Reflection” is a watercolor painted by Angie Porter, who is an artist living in Little Rock. She has worked at UAMS as an interpreter.

By Ruth Fissel

“Going with the Flow” is a photo taken on Ruth Fissel’s land in Jasper, Arkansas. Ruth E. Fissel, LCSW, is the Behavioral Health Program Manager for the UAMS Primary Care and Population Health Service Line.

By Elizabeth Hanson

She is thin, frail, and sickly when I meet her. The right side of her chest is tattooed with a dark purple bruise that spreads up her neck – the aftermath of her port removal. She is tethered to an IV pole by multiple infusions of antibiotics, vasopressors, and fluids. She is bald. Her husband is next to her bed, his skin rough and tanned, shadowed by white hair and a stiff beard. He is feeding her watermelon with a spoon as she smiles when I walk in, her smile lighting up the room.

She tells me that she feels okay today, that she is sore where they pulled out her port, but that she knows it had to go because of the infection. She tells me that she doesn’t mind the bruising, that she thinks it’s even starting to fade a little already. Her husband jokes that it makes her look tough, and she laughs as he offers another chunk of watermelon to her lips. He says he is thankful things are looking better this morning. She says she agrees, and that the watermelon is as sweet as can be. They sit together in the ICU the way an old couple sits together on a back porch sipping coffee at sunrise – as if nothing else matters.

She has cancer refractory to all therapies. Her infection is treatable though, and in three days’ time she leaves the ICU. Her husband walks beside her bed as she is rolled down the hallway. He reaches over the railing and their fingers entwine. She glows when they touch. A cautious smile forms at the corner of his mouth, subtle but suitable. He squeezes her hand, and together they go.

She returns in a week when her kidneys fail. Accompanied by her husband and a friend, she is sleepy and pale and unaware of their presence. A watermelon container sits between them, its lid tightly sealed. She is started on dialysis but she does not get better, her eyes blank and gray. Her mouth hangs open, her death rattle floating through the air, audible from the doorway. Her friend sits in the corner as her husband stays by her bed watching, waiting, hoping, and holding her hand as if this may instill her with new life. He bows his head when I tell him I think we need to talk. Yes, he says, I think that we do.

I expect anger and sadness when I tell him she is dying, that we have tried everything, that the dialysis and infusions and poking and prodding are causing more pain and harm than good. I expect sniffling and tears. But he nods in understanding. He lifts his wife’s hand between his palms and kisses it gently. And then he turns to her friend. How about this, he says. Why don’t we go downstairs, to the café, and split a pizza. How does that sound? Split a pizza and call the family. And then, we can come back to say goodbye. They walk out of the room, and I am left alone with her, surrounded by my thoughts and curious notions of what it means to be human.

Elizabeth Hanson, M.D., completed her residency in emergency medicine at UAMS and is currently a second-year critical care fellow. Outside of work she enjoys writing, drawing, and spending time outdoors.

Poetry

By Ryan Pohlkamp

Spring

An emerald plume in a desolate vale

Alone and young, cold and frail.

A jagged land of the grotesque

A landscape resembling the fields of Death.

A few weeks more and the earth is new.

A sweetness fills the morning dew.

The feathered trumpets return to their place and sing.

Ushering in the months of Spring.

The most precious gift given to all.

I pray that you shall answer the call.

Summer

Stillness consumes the sweltering arboreal hall.

An errant beam streaks the leafy shawl.

A tumultuous city be-stilled by a leaden haze.

Its denizens ensnared in a lustful daze.

Asleep in the shade, lying in the den,

To do anything else seems a sin.

The Sirens of Summer lull the world to sleep.

We follow the bait until we’re too deep.

Awaken! Beware the Songs of Summer!

These days are too precious to loaf and lumber!

Fall

Amidst the sea of green, a conflagration consumes the hill.

From the heavens the rustling flames begin to spill.

Without smoke nor heat, it’s tendrils spread wide.

Bright and intense yet gently abides.

A Sacred Flame, a Holy Thing,

A vivacious requiem for the Sons of Spring.

After, a silent grave draped in a hoary pall.

Nothing more, such is Fall.

A few months a year to flower and thrive.

Then all must reach an inevitable demise.

So ‘Tis better to burn out, I say to you.

Just as the oak and the dogwood too.

Winter

Bleak and gloomy, a frozen sheet over barren lands,

As lifeless and cold as a stretch of sand.

The earth is asleep, gone down to rest.

A life once lived has passed its crest.

Days once long and full of heat,

Are now so short, so cold, so meek.

Distant memories are all that remain.

There to bear fruit, uphold, or profane.

All but some reach Winter’s untimely end.

It is up to you to begin again.

Ryan Pohlkamp is a fourth-year medical student who loves to explore the beauty of nature.

Creative Non-Fiction

By Conrad Murphy

My feet found the steps and I opened the door to Harmony Health Clinic. Immediately I’m flanked on each side by a food pantry and personal care items that patients can take with them as they enter or leave the clinic. A few smiling faces looked up from desks, computer monitors, and folders as I walked through the entryway. These faces either gave up a weekday evening of meeting with friends or a tempting morning of extra sleep on Saturday to be here to work.

“Hey, how are you? How is your daughter?”

“It’s good to see you again, thank you for coming!”

New students have made it too, unsure where to go or what to do. Excitement and nervousness feel exactly the same, so just tell yourself you’re excited. A couple of patients have already checked in and rooms are waiting to be filled. Anxious hands placed stethoscopes around necks and pens in coat pockets. This must be where physicians get their poor handwriting.

With nervousness briefly placed aside, a manila folder full of demographics, chief complaints, medications, and referral notices spilled out for my first patient. Words that haven’t been seen, doses that haven’t been studied. Medical students don’t know what they don’t know. That’s what scares them (me) most. In moments we would be face to face with a patient and charged with helping to address their health without knowing even a fraction of the breadth of human physiology required to arrive at a reasonable diagnosis. It’s daunting, but we didn’t yet know that our lack of medical knowledge was a strength today.

The first patient was a new patient, a mother that cleaned houses for a living and came into the clinic to resolve a recurring rash that spanned her shoulders to her hands. We talked a little bit about the rash and spent the remainder interacting with her children and playing with tongue depressors. The attending provider prescribed a cream and an oral medication with instructions to return in a couple weeks to ensure the rash has gone away. An easy case, straightforward and clear. The mother left the exam room relieved that her kids were thoroughly entertained throughout the whole process.

The second folder was lighter than the first, another new patient. An older woman was there to establish care and hadn’t seen a physician in months. My classmate and I saw her on our own first, to gather all of the relevant information before presenting her case to the attending physician.

“How can we help you today?” The keystrokes sped up and her electronic record started to fill with the story of her health. An older woman with hypertension but otherwise very healthy. I clicked through the different parts of her note, filled in vital signs, and recorded her current prescriptions. Of all of the sections in her note, the “Social History” was the page that I spent the most time on. We found out about her stresses, recent changes in life, even her dreams for the next several years. She was looking for a new place to live and excited about seeing her grandchildren in a few weeks. She was celebrating another year without drinking alcohol and the date of her last drink was a couple months after the day I was born. After gathering our notes we left her for a few minutes to present her case to the attending physician. Only his kind eyes were seen above his mask, but his attention was fully given to us. Forgiving our missteps and scattered thoughts of our presentation he said, “Let’s go see her.”

As we entered the room he greeted our patient with enthusiasm and care. Almost immediate rapport was established as his voice reached her ears. His presence in the room was an anchor for the patient, the foundation of the room built on his assurance and demeanor. I sat silently, typing in missed details that he gleaned from our patient’s story.

As our visit lengthened the nature of the conversation shifts. Our attending probed delicately into her life and the atmosphere in the room changed. It felt as though our physician was gently taking the walls of our patient’s mind down and adding them brick by brick to the walls of our exam room. He was building something new.

“Where are you staying now?” The physician asked.

“With some friends when I can.” she said.

“Where are you staying when you can’t stay with your friends?”

“In my car.”

“How often is that?”

“Two to three times a week,” she said.

At this point in the visit it was glaring how much we missed in our initial visit with this woman. Our assumptions clouded our vision and we forwent vital parts of her history. I stood watching her explain her struggles completely to the doctor. It felt as though a heavy veil fell upon the four of us in the room.

“God has seen my suffering and will bring me through it,” she said. Tears slowly fell down her face and rested on her mask as she looked up at the physician. She, like others who have come into our clinic, walked the streets without any obvious signs of distress or worry. A transparent, heavy veil often fell on our patient with no one else to help distribute the weight. We could never know by seeing her in the grocery store or the bank that her world was slowly collapsing.

She built the walls of her life high because survival demanded it. We all may build our walls higher or lower, but their strength is constant. However, our doctor took the bricks of her wall and laid them down. He poured the foundation of the exam room floor and built a House of Hidden Suffering. A place where burdens or fears are revealed to entrusted souls and are momentarily shared between them. The Christian faith holds that God is The Great Physician. Obviously one that heals, cures, and cleanses, but to our patient it seemed that her God walked alongside her and listened to her. She was telling us that God shared her burdens when no one else was there. As care providers, we’re charged with seeing and confronting realities that the public does not. We’re charged to see what God sees. That burden struck me.

Legally, we’re required to safeguard her records behind locked doors, both physical and virtual. We forget that we must safeguard her suffering hidden in our hearts, to let us be changed by them and to respond appropriately with more than a differential and treatment plan. To be even a good physician, we must sometimes let the veil rest on us.

Walking into the clinic, my classmates and I were most worried about our lack of knowledge. Experience isn’t something you obtain until just after you need it. Although our deficits were obvious, our inexperience gave way to humility. Our minds were free to focus intently on our patient and provide sincerity if not much else. The challenge to me is maintaining that crucial focus while slowly, over years, medical knowledge and experience is gained. I often feel that every time I commit a new piece of medical information to memory, some other memory or experience must be discarded. I dearly hope that I retain the lessons I’ve learned in the house that we’ve built here.

Conrad Murphy is a third year medical student at UAMS who lives in Conway with his wife, Sarah, and two daughters, Reuelle and Reniah.

Fiction

By Umesh D. Wankhade

For the third time in the previous ten minutes, Salma yelled, “Sahil, Sahil.”

Sahil would typically require a few call-ups before getting out of bed. Salma could see the white of her coffee cup’s bottom. She looked at the oven clock; it was 6:12 a.m. She drank the last of the coffee, stood up, pulled out two eggs, an onion, and a slice of cheese from the refrigerator, and began preparing an omelet for Sahil. He likes plain white omelets rather than the ones with veggies, which Salma cooks for him. He also complains that his friends ridicule him for the smell of the food.

“Mom, I love cheese and white omelets, but not the ones with cilantro, onion, and green chili.” He frequently grumbles.

She thought about this for a moment and changed her mind; she put the onion back in the fridge. She decided to make him a white omelet today.

“Sahil, Sahil, please come down. It’s almost time to go to school.”

She yelled one more time; she knew Sahil would come down in a few minutes. She added salt and pepper to the sizzling sound of cracked eggs on a heated pan. When she pulled the spice tray from the cabinet to put the salt and pepper away, she realized that many of the spices she brought back from her most recent journey back from Lahore had not been used in a very long time. Those spices were hand-selected by Ammi from Jinnah Market’s masala galli. Her mother had insisted that she take all the spices with her. She had stocked up on mutton gosht and chole masala, among other things.

“You can’t find these quality spices in your small town of Amrika.”

Salma’s Ammi always thought of Utica, a suburb of Kansas City, as a small town, because she would always hear from Salma how long she had to drive to work, buy groceries, etc. Ammi would always refer to America as Amrika by stressing the middle part of the word.

She picked a handful of cumin seeds and brought it close to Salma’s nose before she smelled and made the sound ‘Aha.’

“It’s not a good practice to sniff things off the street; someone else will buy that same material you just put your hands in. Most likely, we’re buying this stuff where someone else did the same thing you just did”

Salma was annoyed by her mom’s action.

“Oh, come on, baby, don’t act like an American; you are still Pakistani at heart.” Ammi took her banter playfully and went back to picking the best-quality dry dates for her.

She used to go with her Abbu to spice place when she was a child. This time somehow it hit differently. She was visiting Lahore for her Abbu’s inteqal. She had hidden the news of her divorce from him; she did not want to let Abbu down. Now that Abbu is gone and Ammi was aware of this, she felt a bit relieved, but she also wondered how he would have reacted had he known. Abbu never liked Salma’s decision to follow her husband to America in the first place. Salma was the only child they had, and they never wanted to let her leave their sight. After she graduated from dental school, he wanted her to settle down and start a clinic in Lahore, despite all the freedom he had granted her regarding her academics, going out with friends, etc. Also, he was aware of the overall impression a hijab-wearing Muslim would get from a westerner. He tried to explain, but Salma was too preoccupied ‘in love’ to listen to anything otherwise.

She grinned as she recalled all of the wonderful times she had spent with her Abbu. On her way home, in a colorful rickshaw, her Abbu would always stop by ‘golgappewala’. She loved them even though the golgappa would break before she could put them in her mouth and splash all the spicy water on her salwar. She always thought the owner of the golgappewala was the richest man because he owned all the golgappa and a huge pot of spicy water.

“Ammi, I won’t be able to carry all these spices. Don’t buy so much.”

Ammi was busy picking dried red pepper, Kashmiri red powder, Kala jeera, and bay leaves. Even though Salma said that she can’t carry all those spices, she knew that was not the truth. Since she had started working at the neighborhood dentist’s clinic as a dental hygienist, she had stopped cooking anything Pakistani because of the overpowering odor of food. She does not want her patients to complain about the cooking smell of her clothes while she leans on them to clean their teeth. And Sahil, now seven years old, had strong opinions about what he wanted to eat and what he did not. Sahil had come home several times, complaining that his friends didn’t like the food he brought to school. She would occasionally serve him spicy rice with lentil soup. For these reasons, she reduced the frequency of cooking Pakistani food, at least on weekdays.

She had poured herself into American culture, she wanted to ‘fit in’.

She cherished the Chapli Kabab that her Ammi used to prepare for her using meat from halal shops and spices from Masala Galli. Sahil struggles with spicy food. Most of their evenings are spent picking up Chick-fil-A sandwiches and nuggets or grilled cheese and fries from Five Guys. She flipped a rolling cabinet tray and noticed Chole Masala her Ammi had picked. She intended to make chole the following weekend, slightly less spicy so that Sahil could enjoy it as well. He loves naan; if nothing else, he would eat a little chole with naan.

She sensed Sahil’s footsteps behind her. Omelet was almost done; she flipped the sunny side down. Although Sahil would like the sunny side without being sautéed, she would still sauté it. Many a time, she would make these decisions as if they were for her. Oh well, mom would make all of the decisions for a seven-year-old anyway. What do they know? She thought to herself and smiled.

“Momma, why are schools so early? I’d like to sleep a little longer,” he said, hugging her from behind.

“Well, we just had a nice weekend; it’s Monday, honey, so there is a long way to go before next weekend arrives. Then you can sleep a little late on Saturday.” She pulled him from the side while flipping the sunny side up.

“There is a glass of warm water and milk on the dining table. Please finish it as soon as possible, honey.”

He rubbed his eyes and dragged his feet towards the table. Salma had packed his lunch and prepared his breakfast. She hurried upstairs and started getting ready. She grabbed the black scarf from the chair, carefully tied her hair, made a big bun out of it, and covered it with the scarf. She did so hurriedly, with one eye on the clock on the wall.

By the time they got out in the building lobby, it was already 7:30, and she had 15 minutes to get him to school to avoid tardy.

“Hello, Mr. Louise! Good Morning! It’s a new day!”

She yelled cheerfully at the security guard at the door.

“Good morning, Ms. Ali, and a special good morning to you, young man,” he said cheerfully.

Sahil didn’t respond to Mr. Louise’s cheerful voice since he was still groggy.

“How about those Chiefs? They did well last night!” Salma continued their chat.

“Yes, they did extremely well. The next stop is the AFC championship. But I heard that Manning kid from Indianapolis is good. It’s not going to be easy, but we will get it done!”

Mr. Louise alluded to the Kansas City Chiefs AFC matchup with the Indianapolis Colts and quarterback Peyton Manning, a new sports phenom.

Salma did not know much about Peyton Manning. She wasn’t a fan of sports, but to have these types of small talks, she would open up AOL’s sports section on her computer every morning to keep up with the latest happenings in Kansas City sports.

“Good luck to our Chiefs. They will do well. Bye Mr. Louise, you have a great day ahead.”

“Momma, we don’t watch football ever, how come you talk so fondly of Chiefs with Mr. Louise?”

Sahil asked Salma while adjusting his seat belt in the back seat.

“I just like to talk to people, Sahil. And when you are living in a different country, you got to do things they do. You know, you live like a Roman when in Rome!”

Salma looked at her wrist watch; they still had five minutes left to reach his school.

“We can make it; traffic ain’t that bad.” Salma thought she said this to herself, but Sahil’s response told her that she said it loud enough for him to hear.

“Momma, you did it again. That’s not “ain’t”. That’s how Mr. Louise, Mr. Bradley says it. Its ‘traffic is not that bad’ Sahil corrected her as he does from time to time.

“Bye Sahil, be a good boy! Pay attention in class.”

She waved goodbye to Sahil and went on her way to the dental clinic.

*********

After finishing her busy day at the clinic, she checked the time; it was almost 3:20; Sahil’s school would be out in a few minutes. She gathered her stuff and started to leave.

“Bye Salma, don’t forget about the church event this Saturday! I heard they are going to have a bouncy house and a magician!” Julie at the reception desk reminded her of an event at her church later in the week.

“Yes, for sure! I wouldn’t miss it for the world. Sahil is looking forward to it.”

She hurried to get in the car and raced towards Sahil’s school. She was relieved to see a few cars ahead of her in line to pick up the kids.

“Momma, how was your day?”

Sahil threw his backpack and lunchbox in the back seat and made himself comfortable in his booster.

“It was busy but great, honey. How about yours?” She always liked it when Sahil asked her about her day.

“It was not so interesting. We had a sub today. I like Ms. Rudd better. But I guess she had some important work.”

Sahil likes his teacher and expresses displeasure when there is a sub.

“Mommy, can you make those flat meat nuggets today?” Looking out the window at the passing by Chick-fil-a, Sahil said this to Salma.

“You mean chapli kabab?” She was surprised by his request. He usually doesn’t ask for Pakistani cuisine. He enjoys his PB&Js and egg white omelets.

“Yes, that one, the one Naani made last time we visited Lahore.”

“Oh, that’s great! I will try it tonight, we better hurry then, it takes time to marinate the meat.” She will have to stop by an Asian store to pick up some halal meat on the way. She was not going to let this chance go by when Sahil himself had asked for some Pakistani food.

She noticed a man with a white beard and shaggy clothes holding a placard outside while waiting at a traffic light on her way to an Asian store. In that chilly winter of Kansas, a sign in his hand said “Please feed a veteran, twenty-five cents will do.”

It also said something else, although in the fine print. Salma squinted her eyes and tried to read that. It read “I killed those ****** Muslims in Afghanistan and took revenge for 9/11.”

Her heart sank, as soon as she saw that hateful sentence. Although it was not the first time she felt threatened, her hijab attracts people’s attention. Sahil was barely five and in kindergarten when he came home complaining that some kid called him a terrorist because of his name, ‘Sahil Ali’. She seriously thought about leaving the country after such incidents. But her personal situation with her then-husband made her choose to stay.

She reached into her glove compartment, pulled out a dollar bill, smiled, and handed it to the guy on the other side of the window.

The chilly wind and even colder look from him made her shiver! Deep down though she knew that she had to be ‘extra nice’ in this country. Her hijab did not go unnoticed by that homeless veteran. The usual ‘God bless you’ came after looking at her hijab with scorn for about five seconds.

“Why did you give him money? Instead, you should give food.”

Sahil noticed that his mom handed out a dollar bill. His teacher had told him about the food bank for the homeless, and in fact, he had brought some chickpeas and Campbell’s soup cans to donate.

“He can buy the food with that money” She answered Sahil while looking at the back of the veteran.

That evening she cooked Sahil’s favorite chapli kabab, and he loved it. In fact, he wanted some leftovers in tomorrow’s lunch box. She was looking at his calm face when she tucked him in bed.

“Being nice does not hurt and remember we have to be ‘extra’ nice.”

He did not hear her. He was fast asleep!

Umesh Wankhade, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics at UAMS and enjoys running and listening to podcasts/books.