By Conrad Murphy

Everybody has one. Everybody has their person. The one who was “the reason for going into it.” Who knows how many different names show up in each medical school application? Clarke Wesley Johnson. Not born to but adopted by Hans and Judy Johnson; the first boy of the family. He had darker skin than the rest of the household and a large scar from the top of his chest to his belly button.

When I came along much later and asked why, he told me that his parents were Native American, and his scar was a battle wound from fighting off a buffalo when he was a baby. Only half of that was true, but I was too naive to tell which part. That was all I knew about his biological parents, besides the other thing. Their unintended but nonetheless terrible thing they left him with. The thing that made his lungs fill up with what my seven-year-old self described as gunk. The thing that made him take a duffle bag worth of medicines every morning. The reason he couldn’t work at a job, the reason he floated from our house to my cousins’, to my grandma’s, and back. I could pronounce cystic fibrosis at the time even though I couldn’t spell it. CF was a household name for us. For all that Clarke was, it would be best to say that he was my person. My reason.

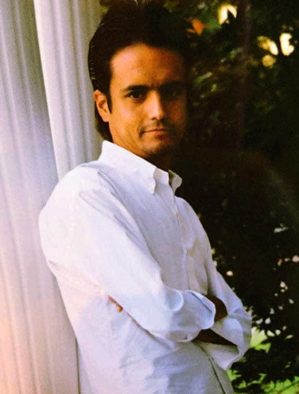

“Uncle Clarke, why do you look so much bigger in this photo?” We were glancing through albums that my mother put together and we came to his section — one picture of him as a child next to my mom and aunts, the other of his high school graduation.

He pointed to the corner of the room where that duffle bag of medicines lay, always in sight. I never knew him without it. During one stretch of his life, he stayed with us in our house. When he was home, he’d take my bed, making me sleep on the top bunk every night. I used to hate that. The land my family owned was his playground — field after field of a cattle farm, ponds to fish in, deer to hunt, hills to ride over. We’d take his metal detector out to the old burned house; we’d walk the boneyards hunting coyotes so we’d stop losing cows to them. Those were the years that I hardly remember him having a cough. Times like that never last though.

Years passed and I found him at our home less and less. I got my bottom bunk back. He would often go to the hospital for tests, back out to Oklahoma with other family. I would see him for one weekend at home, but he was gone the next day because he only needed to pick up a few things.

“Can I come this time? I’ll be quiet and won’t get tired.”

“Not this time, but the next one, maybe,” Uncle Clarke said. The coughing started to increase, not enough for me to notice it at the time, but in hindsight it was more than in the years prior. I found myself taking back the top bunk in case he came home and needed his bed back. Waking up to the bottom bunk still made was always a disappointment.

The first scary day was on the brink of summertime, during my last days of school for the year. I got home and mom was on the phone, getting her things gathered and ushering me back out the door toward her car.

“Yeah, just meet us there, and it will be fine.” She dropped her keys several times on the way out the door.

“Mom, where are we going? I just got home; can I stay?”

“Your uncle is stuck in Alma; he needs us to come pick him up. Michael is meeting us to help drive him back.” Her voice gave a little bit, but she steeled herself when she heard it.

“What’s wrong with him?”

“He can’t drive all the way back to the house, we’re going to get him. Just get in the car, now.” It was a quiet drive, a long drive.

Two and a half hours later we arrived at a gas station outside Alma, seeing to find my uncle leaned back in the front seat of his car. My stepdad and mom helped him walk over to the passenger side door before we all drove back home together.

“Uncle Clarke is going to be staying with us for a while now, so you’ll have to help him if he needs something,” Mom told us. Although I would have much preferred him back without the illness, I wasn’t going to complain.

Life resumed; however, my uncle was approaching two duffle bags rather than one and we stuck to video games indoors rather than running around in the fields all day. He seemed to get better and later invited me to go with him to his hospital visits.

Not many children would enjoy spending the day watching their uncle go through multiple offices, scans, or blood draws, but I enjoyed going. One reason was because I got to spend time with him, and the other was that he always bought me a video game afterward. We got up early in the morning, had breakfast, and I watched him open his duffle bags. I spent the day watching him interact with several doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, and radiology technicians. All of these people were working really hard to make sure my Uncle Clarke could breathe properly.

I walked the halls of the tall buildings at UAMS, and it wasn’t long until I knew my way around easily. My uncle could trust me to go find the vending machines without getting lost and the nurses came to recognize me since we were there so often. I watched him groan as one of the nurses said that he had to complete another breath test. We walked to a different floor of the hospital where he greeted a technician while unenthusiastically handing me his backpack and medications.

“Another one already, Clarke?” she said while untangling some wires and logging into the software for this big machine she had next to her.

“I’m going to be breaking records on this thing if they make me come down here any longer. I’m going to have to really try on this one or they won’t like me upstairs,” he told me as he slipped on a large plastic mask.

The technician gestured to him like they had their own secret language. My uncle nodded and took a deep breath before he exhaled as quickly and completely as he could. His dark face turned a purplish hue for a few moments until he couldn’t breathe out any longer. He swiped a few very fast breaths and took a few moments to recover until he was going again. The technician understood him without any words.

We then left to go to a radiology waiting room and I had to watch him drink something that looked like the glue my mom would use to paste his pictures in the scrapbook we looked through years before.

“This one is grape flavored, apparently,” he said as I laughed, and he giggled and gagged his way through the large bottle. He told me that he had to drink it because they were going to put him through a scan that lights up his lungs to see if they’ve gotten any worse. He told me that the scanner was like a big white doughnut, and it took pictures of him while he was passing through the hole of it. These visits continued and increased over time. I found myself going almost every two weeks toward the end.

It wasn’t long before he started doing worse on the breath tests, and the impressions on the CT scans became longer. I went a full month without going to the hospital with him because he had been stuck there for that long.

“Mom, why can’t they just give him a new pair of lungs? If he had new lungs, he’d be fine!”

“Honey, they already did that.” Suddenly all of the medications and the large scar down his chest made more sense to me.

When my mother came home with doughnuts for breakfast one morning, I knew he had passed away. We only got those when a family member had passed. She walked into my sisters’ room while we all were playing just as the sun was coming up. She explained to us that he loved us very much and wished that he had more time but was happy because he didn’t have to cough anymore and could finally sleep for more than two hours at a time. I just looked down at my doughnut, imagining a tiny Uncle Clarke passing through the hole.

Clarke chose to donate his body to cystic fibrosis research in the hope that gains would be made in the fight against it. We had a memorial service at the Methodist church in my small town. Every part of the service was miserable for me. It was the first time I really understood the cost of death. There was nothing but sobs around our table as we listened to the kind words that were said about him. I remember thinking these words would have meant much more to him if he were alive to hear it. Months later we had a second small graveside ceremony when we buried his ashes. My mom stood consoling my grandmother because she knew that children were not supposed to pass away before their parents, no matter how much longer he lived past the life expectancy for CF. I stared at the small canister on the stand at the head of the grave, trying to envision that it held all the memories, lessons, and laughs of a life.

I considered my Uncle Clarke a second father figure. He instilled life lessons into me. He taught me how to shoot a gun, hook a fishing line, and how to ask a girl for a dance. He didn’t have any advice on dancing, though. The reason his memorial service was so unbearable was because his presence was the complete opposite. He meant so much to people. It wasn’t until much later as a high school senior that I came across a paper weight in a stack of his old stuff. It looked like a glass coaster that you would set a cola can on, but it was engraved with a pair of lungs surrounded by the St. Louis Gateway Arch, the monument of the city where my uncle had his operation. Below the paper weight was a picture of him shaking hands with the doctors who performed his surgery.

As I walk onto the UAMS campus again as a freshman medical student, that image continues to stick in my mind. Some friends ask me, “Why would you want to work in a place like that? It’s where people go to die.” They aren’t necessarily wrong. It is the place where my Uncle Clarke died. To me, it is more of a place that he returned from, over and over. Although they did not cure him, they gave him time. They gave him time to teach his nephew, to make his sisters laugh as he always had, to play video games with his family, to attend Thanksgiving and Christmas gatherings. That handshake in the picture was an understated social transaction between a hardworking uncle who wanted to have as much time as possible and a doctor who wasn’t going to give up trying everything for him. He was my person, the one who got me here. He was the one on my medical school application.

Telling people that I want to work in a place like this is easy because I want to shake the hands of the mothers, fathers, uncles, aunts, sisters, or brothers that only want to teach their kids how to shoot a gun, hook a fishing line, or teach them how to ask a partner for a dance. That’s what I would say now, if we held another memorial for him today, if he were around today. I would tell him that I’m a medical student because of him. Not because he died, but because he struggled. You don’t struggle if you give up — you surrender. He didn’t surrender to CF. He struggled against it and struggled well.

How could I expect to fight for future patients if someone didn’t show me how to fight first?

Conrad Murphy is a first-year medical student in the College of Medicine at UAMS. He lives in Conway with his wife Sarah and daughter Reuelle.